WORKING WOUNDED

Frontline workers become collateral damage in our war against drug use

Erika Weikle struggled with drug addiction for years before becoming a peer support worker at Vancouver Coastal Health (Rafferty Baker/CBC)

LJUDMILA PETROVIC HAS RECURRING NIGHTMARES. Wulfgang (Serina) Zapf is “traumatized, burnt out and exhausted.” Sara Davidson fights the fear of working alone, all alone. Al Black had to give up his dog. Maureen just can’t “absorb the tragedy of these lost lives.” Billy Smith fears finding another dead body at his back door.

These folks are among the working wounded in the battle to overcome our drug use epidemic. They are all frontline workers. There are thousands upon thousands of them.

They work as addiction counsellors, street workers, family counsellors, harm reduction workers, social workers, intake workers, cooks in safe houses and everything else in between. Everything necessary to create and maintain the vast infrastructure we want and need to go up close and personal for us, every day, in the battle to overcome our drug use epidemic. It all takes a toll.

According to Health Canada, at least 2,458 apparent overdose deaths occurred across the country in 2016. There are no figures on the collateral damage done to all those who work to give aid and comfort to those drug users fighting for their lives.

In December 2016, the BC Government and Service Employees Union (BCGEU)launched a workplace survey of those members who were responding to the fentanyl crisis. They got over 250 highly personal accounts of the impact of life lived on the front line of the drug crisis. The BCGEU website features 19 of these stories. Those 19 alone are more than enough to prove frontline workers need and deserve their own particular aid and comfort. Here are some samples from those BCGEU stories:

Wulfgang (Serina) Zapf

I am traumatized, burnt out and exhausted.

I am traumatized because I have to speak to nurses on the phone who, literally, tell me my clients lives are not worth their time and sound surprised when I address their bigotry. I am traumatized because the majority of the public seems to think it is okay for addicts to die.

Sara Davidson

Support workers are not paramedics and often work alone.

A few of the buildings where I work at have 45+ residents. I work alone.

At times, these buildings have been infiltrated and tagged by gang members. Many of these individuals are armed and dangerous. I work alone.

Building rounds are a part of our shift and I have found folks unconscious in the basement, laundry room, stairwells and hallways during my rounds. I work alone.

I mentioned that we are not paramedics because paramedics respond to these incidents in pairs. I work alone.

It’s still impossible to predict when things will go sideways. I work alone.

Al Black

We are no longer permitted to take breaks during our 12 hour shifts. This change has caused worker morale to plummet. I had to give up my dog as I can’t let her out for pee breaks.

It is hard enough to work in some of these dangerous and stressful settings, but not being able to get fresh air and exercise feels like punishment. It is my hope that in the next round of negotiations this “no outside break rule” could be looked at.

Maureen

Death due to a fentanyl overdose being a common occurrence does not mean that it gets any easier to absorb the tragedy of these lost lives. In fact each death compounds the feelings of the responsibility we have to do all we can to educate and prevent this loss.

Many days its like beating your head against a brick wall. Today I provided “Take Home Naloxone” training to a 15 year old drug user and to the Mother who at least had the sense to not punish, but to educate and to be prepared for the worst.

So, I will just do all I can for as long as I can and hope that along the way someone is saved.

Billy Smith

I personally am faced with a fentanyl related overdose or death at least three times a week in the alley where I work. It has pushed me personally to a point where emotions are very easily triggered. And some days I would rather call in sick than chance finding another dead body at my back door.

Laurel Scott

In my field (Community Social Services) workers are getting burned out by this crisis. We are the support to those impacted, but we are also enduring the grief and loss associated with losing people we care for. We can’t go on for much longer. We often don’t have the support needed so we can continue to provide the much needed services to our communities. Then what?

Fran Burgon

We’ve lost so many people this year. Folk who were trying so hard to get free of this opioid. The withdrawal is horrific—more painful than heroin from what I’ve seen. It lasts for ages.

They cry, shake, their bodies go into deep spasms that just don’t stop. They hit themselves, trying to divert the pain to places more manageable than their joints. And it doesn’t let up unless they are sedated heavily.

Fentanyl is getting into everything that is available on the streets. And it’s dirty, so very, very dirty.

For me, there is no giving up and backing down. My team works hard to get people to the right supports, and the right medications to fill those receptors. I’m lucky to work with awesome people who are as passionate about helping others as I am.

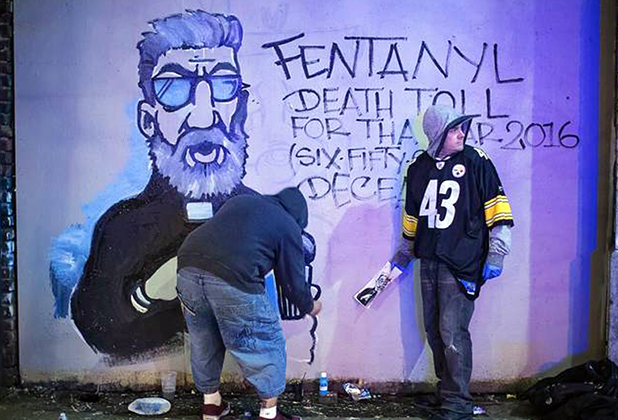

Graffiti artists work on a fentanyl death toll mural

Close encounters of the personal kind

There is a “drug users memorial” outside the South Riverdale Community Health Centre in Toronto. As people died from overdoses, their names were added to the memorial. In four short years, there was no room left for more names.

Death from opioids in Ontario jumped to 865 people in 2016—an increase of 19 per cent since 2015

What the Riverside community memorial does not mark are the working wounded in our war on drugs: the frontline workers.

Unlike paramedics and other first responders, frontline workers often have close personal relationships with those they help. They often spend months, if not years, working with specific drug users. They often save their lives more than once. This makes the deaths more like a friend dying than a patient or “client.”

“We become an extension of their lives,” says Zoë Dodd, who is a harm reduction worker in Toronto. “We organize people’s funerals, we go identify their bodies, we do everything. We go clean people’s homes out, contact their next of kin, so we end up doing a lot of emotional labour.”

Dodd oncew left her job to ease her stress. “I stayed at home in bed, crying all day long, really trying to heal, feeling really sad.”

“How much grief can you take? I really care about people. It’s not easy, it’s fucked, and with all the government inaction it feels like it’s not going to end.

Many frontline workers show all the signs of suffering from PTSD. But they are often unable to get the therapy that would help. Contract work with part-time and casual hours is common. Thus many in need of mental health support simply cannot afford to buy the care they need.

On top of all that, the frontline workers in British Columbia have to pay out-of-pocket for naloxone kits to save users from an overdose, while officially recognized first responders such as police got the kits for free from the government.

Government slouches towards action

Dodd, helped create the Frontline Worker Support Group in Toronto. The group meets regularly and gives frontline workers from different workplaces a space to talk with each other.

An open letter from 700 harm reduction workers, nurses, doctors and academics from 59 towns and cities in Ontario last August got results. The letter called on the provincial government to declare a public health emergency, as B.C. did in April 2016.

In response, the Ontario government announced it would spend an additional $222 million over three years to address the crisis, with $10 million of that to hire more harm reduction workers.

It isn’t yet clear if the funding will include new support for frontline workers struggling with mental health issues as a result of the crisis.

- 30 -

• BCGEU fentanyl crisis workers’ full stories

Add new comment