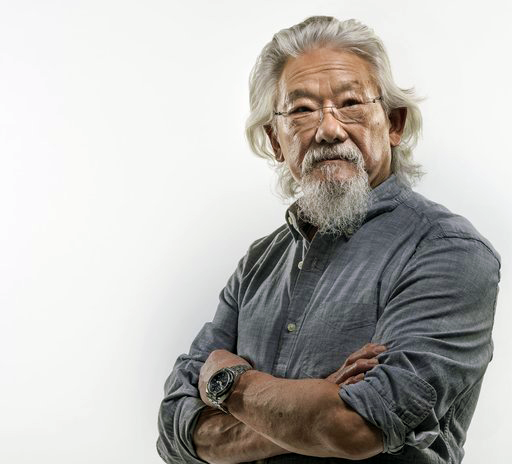

ACTIVIST PROFILE

DAVID SUZUKI: The truth of things

DAVID SUZUKI NEVER HOLDS BACK. That’s not how he got to be a TV star, Canada’s leading environmental activist hero and number one climate-change opponent. He is passionate about the truth of things. He has little time for those who are not.

He once told a professional critic of environmental activism to just “f**k off.”

He calls mainstream economics a form of “brain damage.” He wants us to jail political leaders who deny climate change for “intergenerational crime.”

David Suziki doesn’t suffer fools gladly. The fools never liked it. Suzuki never cared. He still doesn’t.

Calls Trudeau a ‘liar’

He’s 82-years-old now. It makes no difference: “I’m going to be much more outspoken in the coming election cycle,” he said in February 2018.

“Trudeau is a liar. For me, that’s the charge. He’s an out-and-out liar. I don’t think he deserves a second chance.”

—————————————————————

DAVID SUZUKI IS THIRD-GENERATION CANADIAN. He was born in 1936 in Vancouver. At the age of six he was confined with his mother and two sisters in one of Canada’s infamous internment camps. At the end of World War II, the family was forced to relocate to Ontario.

For all of that unsettled childhood, Suzuki flourished. He earned his PhD in genetics in 1961—well over half a century ago. In 1969, he won a Steacie Memorial Fellowship as Canada’s best young scientist. He has since been awarded some two dozen honorary doctorates.

But for Suzuki, popular science education—the engagement of the scientific community with the public—has been his focus almost from the beginning. He continued to teach and do research as a genetics professor at the University of British Columbia from 1963 until 2001, but rose into public prominence via radio and television, beginning in 1971 with the CBC series, Suzuki on Science.

Suzuki was the creator and first host of the well-known CBC radio programme Quirks and Quarks, still running after 43 years. He has hosted CBC television’s The Nature of Things since 1979. In 1985 he created a highly popular eight-part CBC special called A Planet for the Taking. It acquired a wide audience—1.8 million viewers per episode—and won a United Nations Environment Programme medal.

He also worked internationally, with the BBC in Great Britain and PBS in the US, to produce a series in 1993 called The Secret of Life, and with the Discovery Channel in 1994, narrating a documentary called The Brain: The Universe Within.

And he kept writing books—more than 50 of them, 19 of those for children.

His mission obviously ran in the family, because his daughter Sarika, a marine biologist, began to work with him on a number of joint ventures, beginning in 2008 with The Suzuki Diaries, a sub-series of The Nature of Things, which focussed on environmental sustainability issues.

Suzuki’s output of written and visual material is prodigious. The steady stream of honours and awards that have flowed his way for decades includes: Five Gemini Awards; the John Drainie Award for significant contributions to broadcasting; a lifetime achievement award from the University of British Columbia; the Royal Bank Award, offered to those “whose outstanding accomplishment makes an important contribution to human welfare and the common good”; the UNESCO Kalinga Prize, for outstanding contributions in communicating science to the lay public; an Officer, and then a Companion of the Order of Canada.; the Right Livelihood Award, known as the “Alternative Nobel Prize,” established to “honour and support courageous people and organizations offering visionary and exemplary solutions to the root causes of global problems.”

AS REMARKABLE AS ALL THAT IS, that's not why David Suzuki is so deeply lodged in our Canadian consciousness. It is his unabashed love of the earth and all living things that has done it. It is his lifelong proud and passionate environmental activism that has done it.

His awareness of dangers to the environment, he says, goes as far back as Rachel Carson’s 1962 epic book, The Silent Spring. He began his own activism in the early 1980s, opposing forest clear-cutting in what is now Haida Gwai. As a public intellectual of long standing, it was perhaps inevitable that Suzuki would move from a relatively restricted engagement with viewers and readers to organized advocacy and (as an individual) outright agitprop to save the world we live in.

In 1990, he founded the national non-profit David Suzuki Foundation, stepping down from its Board of Directors only in 2012. The Foundation’s mandate, “we work to conserve and protect the natural environment, and help create a sustainable Canada,” would seem inoffensive enough. But he became a favourite target of the Right for his strong views on climate change—and for what he believes must be done about it.

Suzuki’s straight talk can be provocative. He has compared oil extraction with slavery, for example: in each case, he says, proponents have argued for the status quo by claiming that abolition would harm the economy. He is adamant that oil from the Alberta tar sands should be left in the ground.

That was one swift kick to a very large hornets’ nest, and the reaction was swift and brutal.

Though he had been voted the country’s most trusted Canadian in a 2011 poll, and even with his outstanding record of achievement, Suzuki found himself up against Big Oil, climate-change denialists, fringe right-wing commentators—and, at one point, the federal government.

Those who opposed oil sands production in Alberta were labelled “radicals” and “extremists” by the Harper administration. Harper weaponized the Canada Revenue Agency, which set out in 2014 to impose expensive and time-consuming audits on environmental and other progressive charities—including the David Suzuki Foundation.

Suzuki was lampooned by columnists and bloggers as “a little man,” “not a scientist,” a liar, a hypocrite and a fraud. One writer even claimed that his Foundation was an agent of a foreign power (the US).

In fact, all of these crude attacks evaporate pretty quickly when the facts are presented, but that hasn’t stopped his increasingly frenzied detractors. “I’ve had critics all my life,” Suzuki says, “but I certainly think the intensity and vileness of the personal attacks has changed.”

When the University of Alberta took the bold step this year of offering Suzuki yet another honorary doctorate for his long service to science and science education, donors withdrew, the dean of engineering publicly denounced the move as an attack on “Alberta values,” and one prominent university economist, still irked by the “brain damage” comment, said he wouldn’t share a stage with him.

Suzuki’s frustration with this sort of thing has grown over time. “Many of the battles that we fought 30 or 35 years ago… we celebrated as enormous successes,” he said in 2013, but “the same damn battles have started again.” He shows no reluctance to engage in them, though, taking on new environmental challenges like the Kinder-Morgan pipeline and the Site C dam in BC with his trademark gusto and plain speaking.

“I hope there’s a happy ending,” he says. “That’s all I have left. Hope.”

Well, that and his unceasing energy and vision, not to mention his stunning record of achievement—a bequest for the generations to come, and, by most, one that will be gratefully received.

- 30 -

Add new comment