VALUED VOTES

Electoral reform delivers better government wherever it’s tried

Nicola Sturgeon, leader of the Scottish National Party

YOU CAN FORGET THE RUMOURS ABOUT ELECTORAL REFORM. A change to proportional representation (PR) does not bring instability, uncertainty, and political conflict. A quick look at countries using a PR-based voting system proves it.

The truth is countries where a PR-based system is used get a fairer picture of the public’s political views. Even better, they are just as likely to produce more stable governments than the much-vaunted First Past the Post (FPTP) voting system.

Scotland and Wales

In 1999, the first elections were held to the newly-created regional Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly. Much like Canadian provinces, these institutions are in charge of education, healthcare, and social policies in their respective regions. A mixed-member voting system was chosen for the elections to both legislatures.

In Scotland, this means that each voter casts two ballots, one for a direct candidate and another for a regional list. The parliament is then made up of 73 constituent MPs, who are elected using FPTP, and 56 MPs from regional lists.

The list vote is designed to ensure that parties which receive a substantial share of the vote are fairly represented, even if they fail to win local constituency votes, which use FPTP. So, for example, in 2003, when the left-nationalist Scottish Socialist Party attracted around 7 percent of the vote due to its opposition to the Iraq war and calls for more social spending, it won six seats on the regional list.

This is just one example of how a PR voting system ensures that minority viewpoints have a voice in parliament. Another is the role of the Green Party, which between 2007 and 2011, and again from 2016, was able to advance some of its policy proposals in exchange for supporting the government on key votes.

Full-term governments

In the five elections that have been held since 1999, each has resulted in the establishment of a coalition or single-party government that served a full term. These included two coalition governments between 1999-2007, involving the Labour Party and Liberal Democrats. As a result, these governments were more representative than under an FPTP system. More than 46 percent of voters backing one of the two governing parties in 1999.

From 2011-16, the Scottish National Party was able to form a majority government. However, unlike in an FPTP system, where a party gets to do this when it receives 40 percent of the vote or less, the SNP’s majority came about because it secured over 45 percent of the popular vote.

New Zealand

Elections in New Zealand operate under a similar mixed member system. Since elections are held every three years, there have been seven elections since 1999, which have produced two governments.

Between 1999-2008, the government was led by the Labour Party. However, because its majority was dependent on the support of smaller parties in parliament, it was forced to negotiate policy priorities with other parties after each election, in 1999, 2002, and 2005. This meant the electorate had considerably more influence over the structure of the government and the policies it pursued, and that a more diverse range of voter preferences were included in government policy.

For example, when the Labour Party’s vote fell to around 41 percent in the 2005 election, it had to reach agreements with the New Zealand First and United Future parties, which together represented about 8.5 percent of the electorate, to stay in power.

It was a similar story when the conservative National Party formed government from 2008-17. After securing 44 percent of the vote in 2008, the National Party had to reach confidence-and-supply agreements with two smaller parties that accounted for 6 percent of the electorate in order to have a majority.

The experiences of Scotland, Wales, and New Zealand over the past two decades demolishes the claim that a proportional electoral system must always bring political instability. In fact, the governments established in these three countries since 1999 appear comparatively solid when considered alongside governments in countries still operating with an FPTP system.

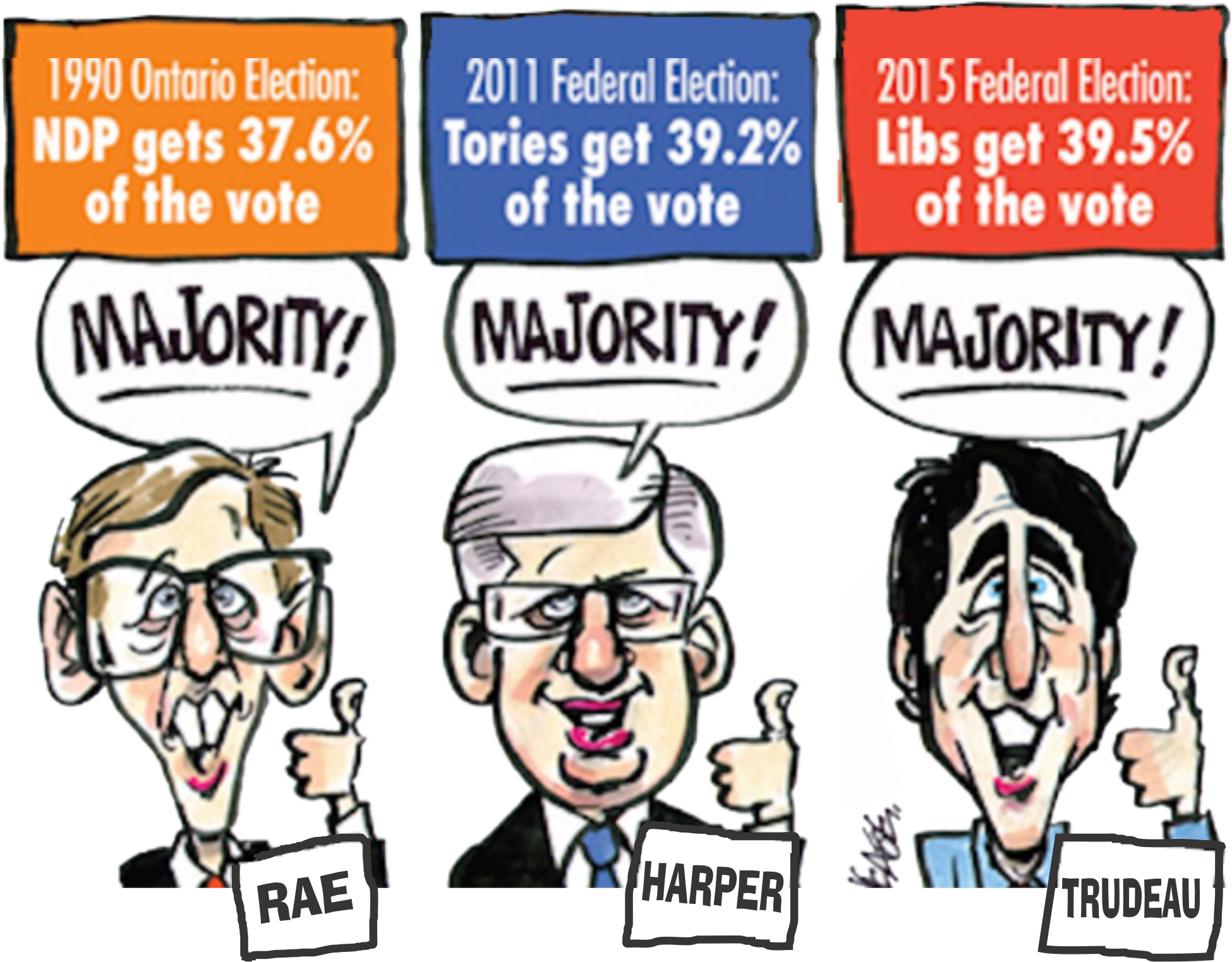

The Canadian way: minorities we call majorities

In Canada, on the other hand, our FPTP system brought the election of a minority Tory government in 2006 and initiated a period of political uncertainty that gave us three general elections take in five years.

In the midst of this, at the end of 2008, the minority Harper government suspended parliament so as to prevent a majority of MPs from bringing down the government in a non-confidence vote.

In Britain, two FPTP elections within two years, in 2015 and 2017, led to the election of extremely unstable governments: the first a slim Conservative majority and the second a Conservative minority propped up by the Democratic Unionists, a regional party from Northern Ireland.

Many observers expect that the current British government, in power for little more than a year, won’t survive the ongoing talks on the UK’s exit from the European Union, never mind a full electoral term.

FPTP gives old-line parties stranglehold on power

The reality is that there is no basis for the worn-out arguments constantly brought forward by supporters of the status quo in Canada. There is no indication that FPTP provides better protection against political instability than an alternative electoral system based on PR.

Nor is there any indication that PR systems, which require voters to fill out two ballots, are too complicated to be understood. In both Scotland and New Zealand, voters have shown themselves to be more than capable of removing parties from government through the ballot box when they have become unpopular.

The only reason that remains for the major parties to defend FPTP is out-and-out self interest. For the Liberals and Tories in particular, the continuation of the status quo enables them to dominate political life, even if on a good day they rarely come close to capturing a majority of the popular vote.

This is why a push for electoral reform must emerge from activists and organizations whose main concern is securing the democratic rights of the vast majority, rather than the monopoly on power enjoyed by the major political parties. The goal of such a movement should be for the first-past-the-post electoral system to be voted out!

- 30 -

Add new comment